My Dad was an amateur photographer. When he died 20 years ago, I inherited his boxes of slides. My Mom died in 2017. I’ve got her pictures now, as she was an amateur photographer, too. Between the two of them and the volume of slides and prints (neither of them ever adapted to digital photography technology) the number of images through which to sort is staggering but I hope (and trust) that the search leads to a few treasures. Although I’ve been slowly going through them, culling and organizing, there are still thousands of images remaining. I have my work cut out for me.

But this is not a story about my parents or their photography skills. Rather, I’ve become fascinated with snapshots and their inherent value.

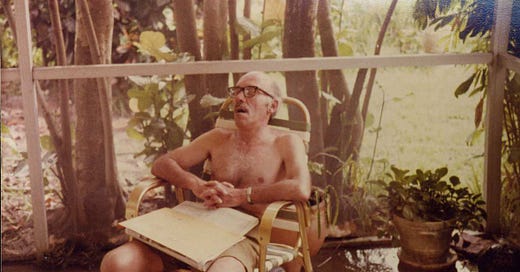

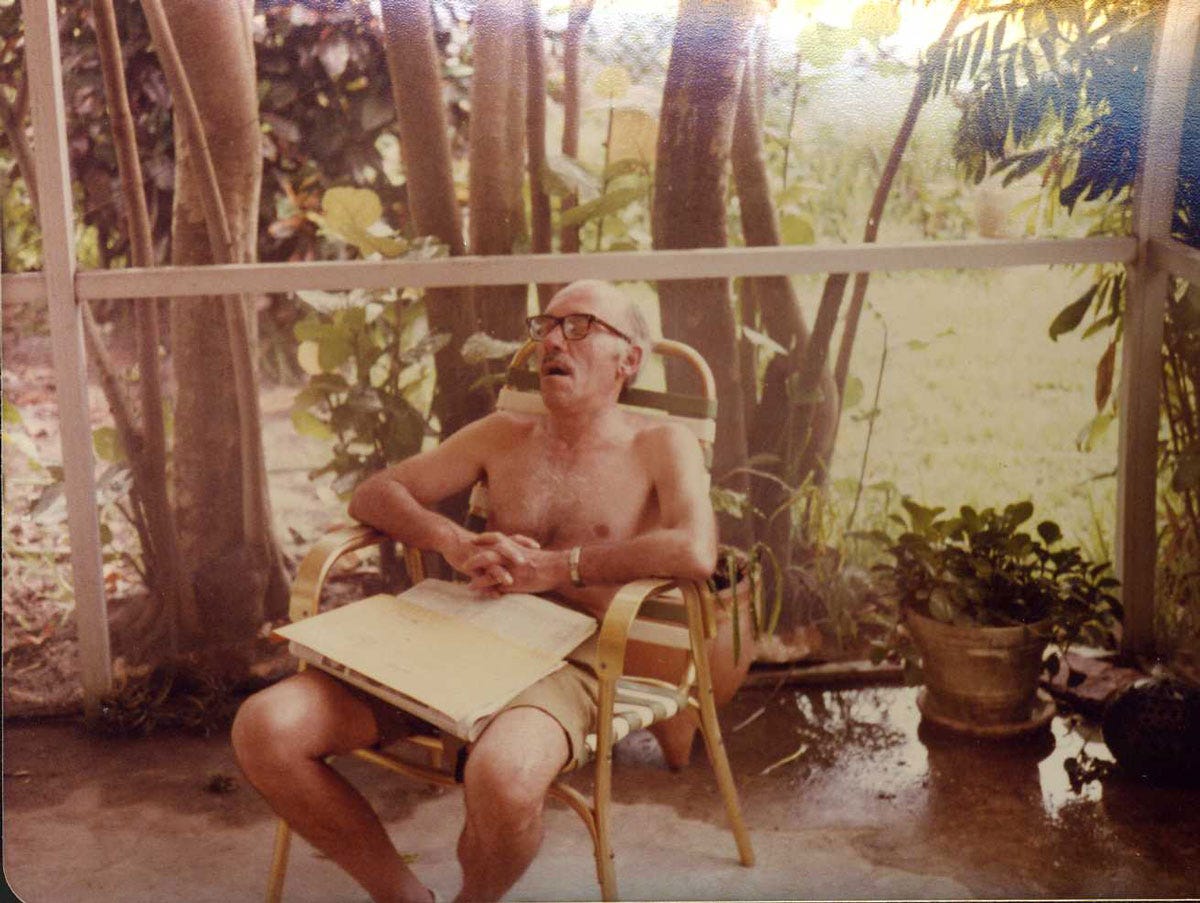

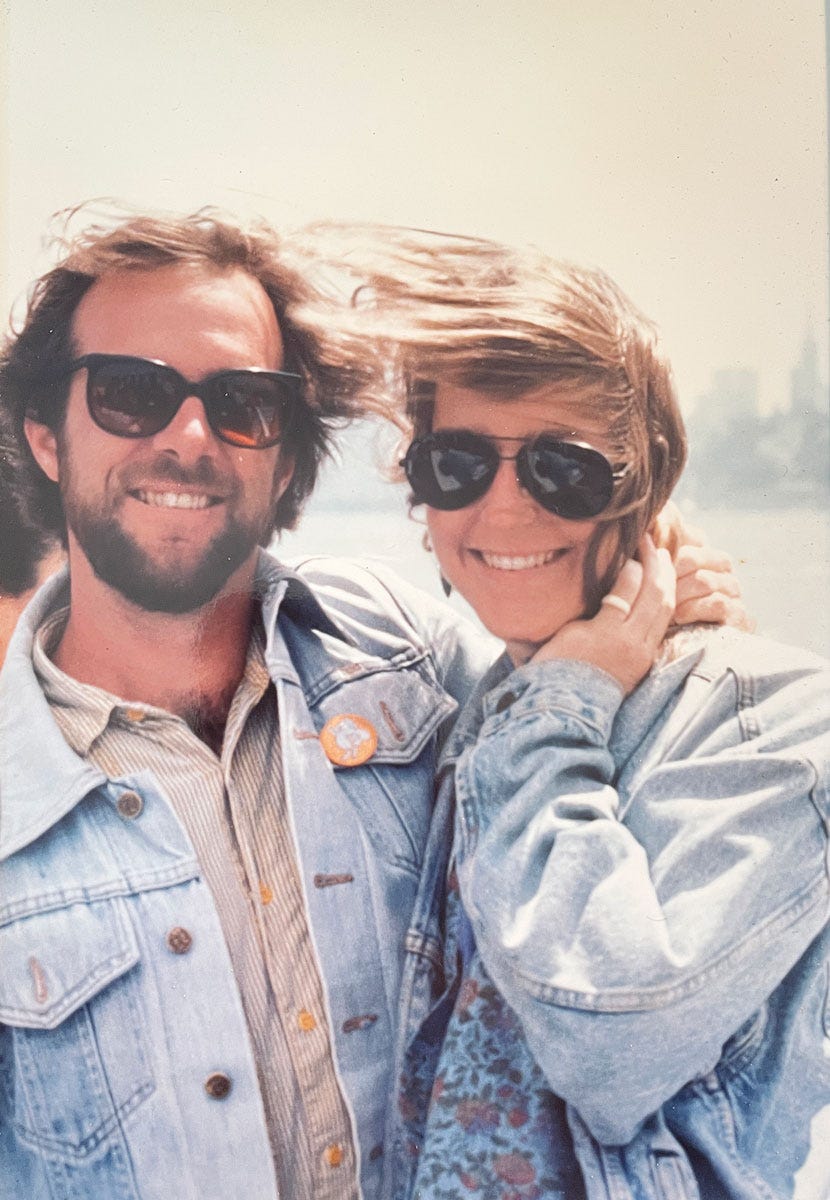

Wiki defines a snapshot as “a photograph that is ‘shot’ spontaneously and quickly, most often without artistic or journalistic intent and usually made with a relatively cheap and compact camera.” It’s a definition that narrows the value and scope of the snapshot. As I’ve gone through my parents’ snapshots, I’m fascinated by the story they tell: the two of them as youngsters, then as kids falling in love, my siblings and I growing up, and finally Mom and Dad in their maturity. Individually, those images are mere points in time but collectively tell a story unique to my family.

I suspect we all find our stories in the snapshots we’ve accumulated over generations. But those images come with a cost. Specifically, sorting through those old snapshots requires an emotional investment, sometimes grief, sometimes delight, but always discovery. Sorting through them, curating and discarding duplicate, over/underexposed, or simply poor images adds to that cost.

Snapshots sometimes come with scribbled notes on the back, or a date recorded on the margin, but rarely with any extended caption. As a result, we make up the stories to go along with an image: “that’s Mom in high school” or “that’s Dad when he had hair.” Inevitably, though, a snapshot will prompt questions. And sadly, more often than not, unanswerable questions.

So, is the lowly snapshot truly “without artistic or journalistic intent?”

The intent may not have been to create art, but those snapshots are artistic nonetheless. The memories preserved tell a story of my family, prompting questions of who they were in those days, and who they became. The first of my parents’ images date from the early 1950s, a time that coincided with widely available cameras specifically marketed for mass consumption. I’m fascinated by the images of those two people in the days when they were falling in love before they were married, before they became parents. That’s the Mom and Dad I’ll never know, the young and carefree lovers, before careers and kids occupied their every waking moment. If art prompts mystery and discovery, then snapshots create a space for that wonder. And if not made with journalistic intent, why were they taken at all, if not for future generations to view, trigger memories, and create a narrative, personal or otherwise?

Those narratives can also prompt scholarly examination. In 2007, the National Gallery of Art mounted an exhaustive exhibition dedicated to the snapshot, The Art of the American Snapshot, 1888-1978: from the Collection of Robert E. Jackson. Kodak’s development of a simple, portable, and relatively inexpensive film camera (slogan: “You press the button, we do the rest”) allowed regular people to record their daily lives that, over the next century, produced billions of images-images today regarded as “historical artifacts.” Film based snapshot photography has given way to the digital age, but the impulse to record and share daily life still drives the urge to take snapshots.

Seattle-based art historian Robert E. Jackson has collected thousands of American snapshot photographs from the late 19th century though the late 1970's. Captivated by the range and creativity of amateur photographs, Jackson’s collection, acquired at flea markets, art fairs, and online, these snapshots are separated from their original context, stripping them from their personal meaning, allowing the viewer to regard them dispassionately, objectively.

But are they art?

In a 2015 interview, Jackson seemed to suggest that snapshots can indeed be considered art.

“I feel that snapshots can get close to capturing the essence of humanity. They deal with the unspoken and unnamed. They often emphasize the aloneness and alienation and underlying sadness of life. But snapshots can also evoke the ineffable joy of life. They are often the visual poetry of the human condition. And there is always an undercurrent of bitter sweetness as they were taken to be a surrogate for memory. At the same time, I think they emphasize how much we need to establish a sense of belonging in this world.”

Several years have elapsed since my parents died and I’m now at the age where many of my friends’ parents are passing, too. And they may be facing the same arduous task of sorting through old photographs, as well. But the passage of time is not just about loss, it’s also about joy, as babies begin to arrive for the generation following mine. I’m currently on a text thread featuring dozens of iPhone images of a new baby girl born into our extended family. (Think of the hundreds of pictures they haven’t shared)! Though they may only elicit a quick ‘like’ and/or comment only to vanish into the ether, I imagine tiny Ama in her (eventual) old age perusing those snapshots on the cloud, prompting the same thoughts, questions, and emotions.

The question of how those images are stored comes to mind, though. I have boxes of physical photographs to sort through: no additional technology required. Will tomorrow’s technology allow us to view images taken decades earlier? Will my future grandkids linger over a photo, taken by my Dad, of my wife and I at the beginning of our life together? Will that image, that spans the lives of two generations, inspire the same thoughts and feelings in future generations? And though it may now be found online, how will the thousands of other snapshots that have not been digitized be viewed?

My inherited snapshots are like a unique archeological record of my family; a history replicated millions of times over with other families. But if the advent of portable, point and shoot cameras made documenting our families’ histories possible, the cell phone with its powerful camera capabilities has expanded that capability in limitless ways. But that’s a different story.

More later…

Great essay, Mark! Very thought provoking ruminations on the intrinsic value of the Kodachromes and Polaroids of your youth.

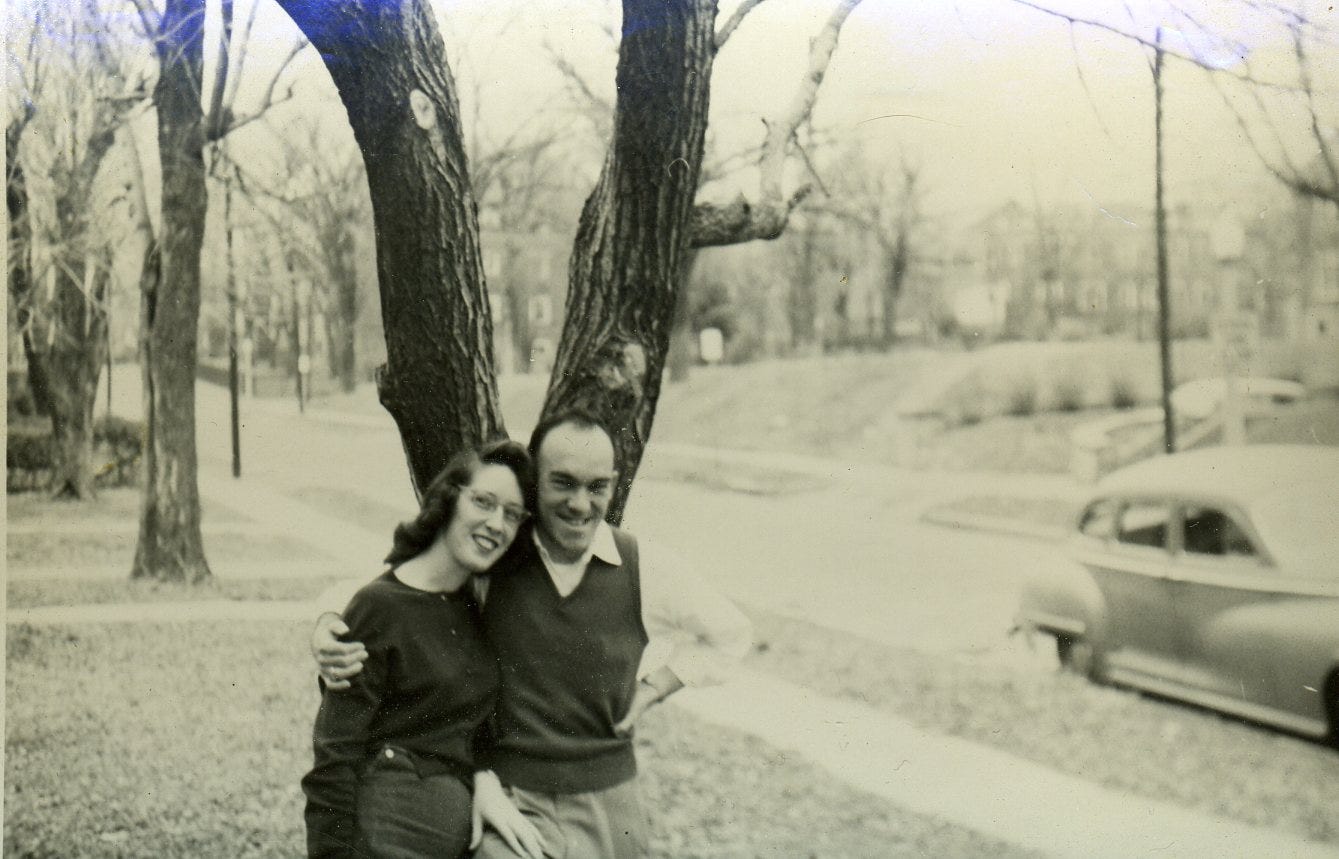

My dad really got into photography, and even developed his own B&W prints in a makeshift darkroom when we lived in Venezuela. He documented our family's history in photos, not all of which I would call "snapshots" because many were taken after several minutes of fussing with the lighting, the camera settings, the "set", and of course, an uncooperative brood of rugrats whom would refuse to hold still, smile on cue, or even look in the general direction of the camera.

Every "wasted" shot back then was a frustrating experience, a negative that had to be developed and likely printed before the hapless photographer could see just how bad the photo was. But even those "bad" shots have some historical value; they captured our capriciousness, our rebellion, our discord. I treasure those bad shots as much as the good ones. Reality, warts and all.

Today's photographers are spared that angst; a bad shot on "digital film" costs nothing.

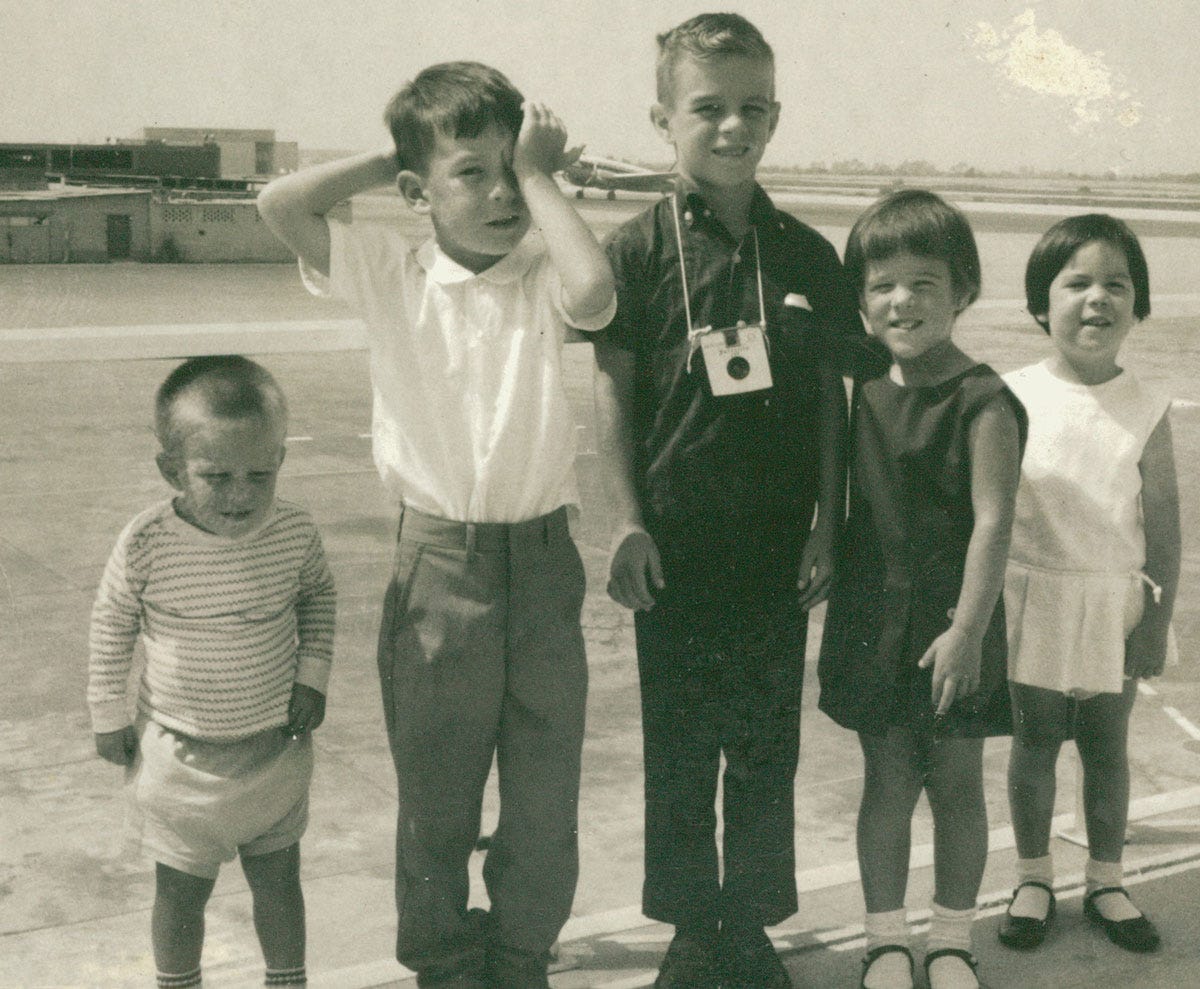

My dad also made copies of photos from his and my mother's parents' archives, so I have the benefit of 3 generations' worth of very old photos, when families would dress in their Sunday best and go to a photographer's studio to pose in a covered wagon, or in front of their prized new automobile. Smiles were rare, which led me to think as a child that my ancestors were unhappy people who lived in a black and white world I could scarcely imagine. But seeing the faces of my grandparents and their parents, frozen in time, yet bearing an unmistakable resemblance to my parents and my siblings, created a connection that makes those old photos precious.

I think that art is in the eye of the beholder. Mark, I enjoyed your post on the snapshot. Snapshots can be art, and so much more.