Of the many things I love about photography, its capacity to track change(s) over time is one that thoroughly fascinates. Sure, we love seeing snapshots of our kids growing up, or our own childhood pictures that remind us of our own changes, but as a history buff I’m especially drawn to vintage photography made by giants of the craft: Robert Capa, Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dorothea Lange, Nadar, and so many others. And though a photograph merely represents reality, it nonetheless depicts a point in time that’s real and true, and that serves as a historical signpost.

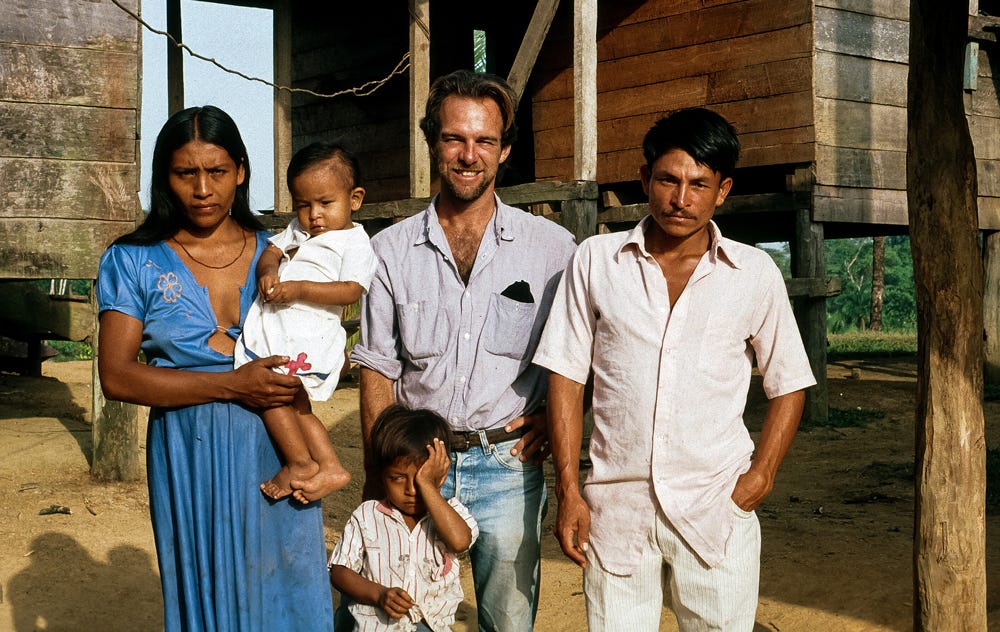

During another life as a graduate student conducting field research in the northeastern Honduran wilderness known as La Mosquitia, I first learned about the scientific basis of using photography as an ethnographic tool and a method for tracking/measuring change. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method (1967) by American anthropologist John Collier Jr., (1913–1992) provided invaluable guidance on how to use still photography in ethnography as an applied research tool.

Some decades earlier in Bali, Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson had experimented with film and still photography to systematically study human non-verbal behavior and movement. This early "visual anthropology" grew over the succeeding years as the technology became lighter, cheaper, and easier to learn and operate.

Visual anthropology involves production (anthropological media, ethnographic films, exhibitions, and photography) and analyses (surveying and finding meaning in existing media to inform anthropological inquiry), conceptually connecting the study of human perception and imagination, audiovisual media, and ethnography.

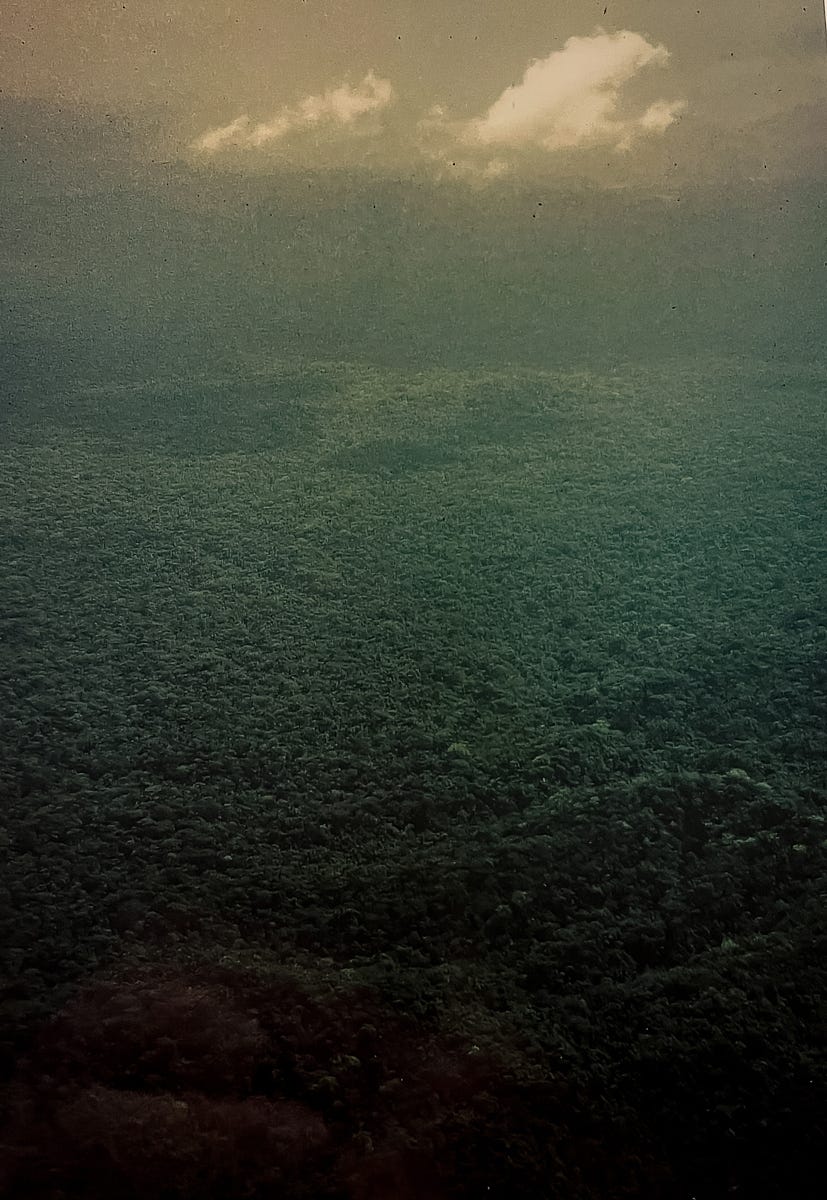

In “Fields of the Tzotzil: The Ecological Bases of Tradition in Highland Chiapas” (1975), Stanford anthropologist George Collier demonstrated how aerial photography is an effective tool for analyzing land use patterns and long-term ecological change. Collier’s work inspired my research with La Mosquitia’s Tawahka Indians using still photography to document 1) the region’s ecology, 2) specific land use activities, and 3) to preserve and confirm details not recorded in my field notes.

But enough about academia. Lending scientific legitimacy to photographic documentation of social and environmental change is vitally important, but photography can also serve a less rigorous but highly creative, artistic role in documenting change.

Several years ago, Washington, DC based photographer, Karen E. Ramsey, produced a series of before/after images of local landmarks she had made over the span of several years. As much an exercise in nostalgia as urban anthropology, her images highlight, as George Collier theorized, changes in land-use patterns. Karen, a dear IG friend and wonderful photographer, passed a few years ago but her work can still be found on Instagram.

Filmmaker and photographer Vivian Wang and musician Catherine Popper (Puss n’ Boots) used the same technique to great effect in Cat’s video for “Maybe It's All Right” while documenting historical changes in New York City. Using a pop song to disguise the video’s intellectual focus was/is genius.

As I explore my new home in the Pacific Northwest, my visit to Clayton Beach just south of Bellingham, Washington was a lesson in natural beauty and the region’s history. These photographs, the first taken over a hundred years ago, depicts an environment virtually unchanged today, yet paradoxically, shows how human intervention nonetheless has dramatically altered it.

Beyond the crabs, lizards, shells, sand dollars, and driftwood, I was struck by the pilings remaining at the southern end of the beach. The ruins of the cross-over trestle of the interurban trolley and the Great Northern Railroad lines are a stark, and startling, contrast to the wildness of Clayton Beach itself-and make for a fascinating photographic opportunity. The photograph made by Daniel E. Turbeville ca. 1911, and housed at the Center for Pacific Northwest Studies in Bellingham at Western Washington University, shows the operational trolley support structures as they were early in the 20th century.

But those land use patterns continue to change. The Northwest Straits Foundation (NWSF) has been tasked with the Clayton Beach Nearshore Restoration Project, a multi-phase project that will remove the historical debris. Although the ruins make for striking visuals, the project will remove the shoreline armor and pilings to “improve sediment transport processes and allow for landward translation of eelgrass beds and nearshore habitats to adapt to sea level rise,” as noted by the Pacific Marine and Estuarine Fish Habitat Partnership (PMEP)

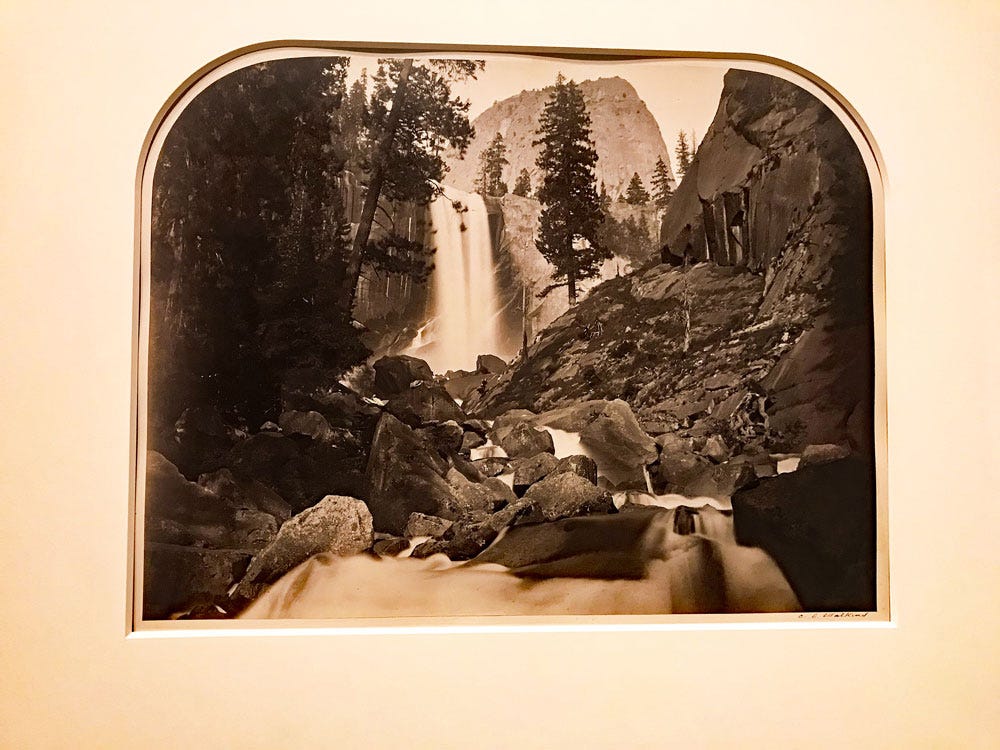

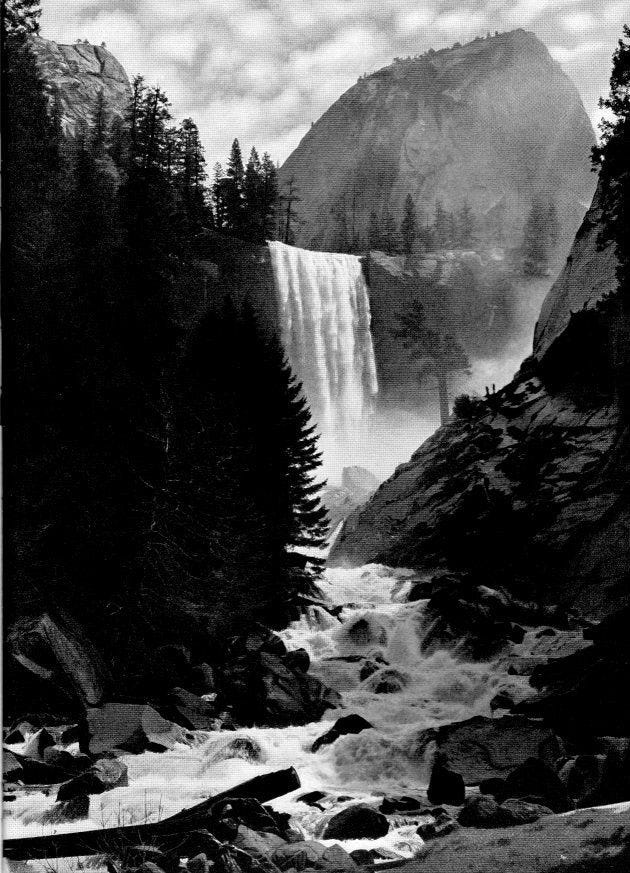

A few years ago, I discovered that an image I’d made put me in the company of giants. I’d taken a photograph of Yosemite’s Vernal Falls in 2004, only to discover (years later) that Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams had made the same image from the same vantage point years earlier.

But if my image puts me in the company of great American photographers, then I share that honor with millions of other people. Ichigo Ichie (literally, "one time, one meeting") is a Japanese cultural concept that invites one to treasure the unrepeatable nature of a moment. Commonly translated as "for this time only," or "once in a lifetime," it is the ultimate invitation to live in the moment, to cherish any gathering, citing the fact that any moment in life cannot be repeated; even when the same group of people get together in the same place again, a particular gathering is unique, and thus each moment is always a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Over nearly a century and a half, millions of visitors to Yosemite, many of them photographers, have shared that once in a lifetime experience of gazing upon Vernal Falls from the same vantage point. A shared, yet completely unique experience made so by light and shadow, the strength of the cascade, and a dying great tree.

More later.

Really good post. Well written and fun to read

Thank you for this post, Mark. This really resonated with me: “Ichigo Ichie (literally, "one time, one meeting") is a Japanese cultural concept that invites one to treasure the unrepeatable nature of a moment.”

That is certainly how I view many of the moments I capture; they are in many ways ephemeral, certainly transitory, and never to be again. Photographs are like little treasures, to be collected, enjoyed, and shared.