“Don't delay, our day is short, you can't afford to wait

So take that laminate out of your wallet and read it

And recommit yourself to the healing of the world

And to the welfare of all creatures upon it

Pursue a practice that will strengthen your heart.”

“Postdoc Blues” John K. Samson

Besides not working, retirement offers many benefits, the chief of which is the opportunity to take stock of life choices, results, and the consequences. Having just passed my two-year retirement anniversary, I’ve enjoyed ample time to ponder those choices and their subsequent outcomes, good or bad.

I was privileged and lucky to have a career in public service. Either by design or happenstance I can’t really say, but somehow I landed in the international development arena, and specifically, grassroots development.

International development, sometimes disparagingly referred to as an industry, conjures images of huge infrastructure projects, multinational contractors, and millions in funds disappearing into offshore accounts, certainly has its efficiency and ethical issues. But international development also attracts individuals who are driven by purely altruistic motivations, people who want to make their little corner of the world better (h/t Hawkeye Pierce). Peace Corps, that little U.S. government agency that has supported over 240,000 Volunteers in 144 countries since 1961 trying to make their little corners better, was where I learned about grassroots development; the notion that people in poor countries recognize their own problems, and more crucially, how to fix them. What they need is technical support, skills training, and most importantly, money. Maybe trusting project management to the local population is a foolhardy venture, but it simply shows there is a willingness to take risks and support local solutions. Some may call that subversive but for many of us, Peace Corps validated that spark of daring, teaching us that a little subversion is not always a bad thing.

Growing up in the U.S., Peru, and Mexico gave me an appreciation for cultural variation, tradition, and language. Studying anthropology in college was not a random choice but a direct result of my international upbringing. Following graduation, I chose to join Peace Corps, not just to help people, but to satisfy my curiosity about other countries and cultures. I remember telling the recruiter I wanted to get out of the country now that Reagan had been elected President. He chuckled and recommended that we should probably leave that motivation off the application. Apparently, I was “woke” before it was cool, if not politically naïve.

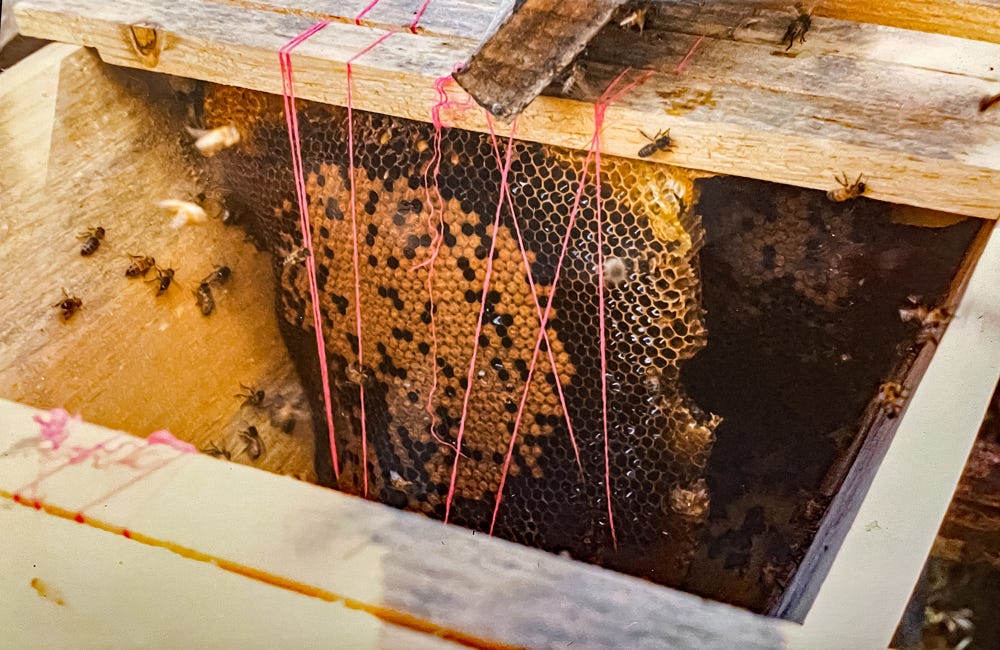

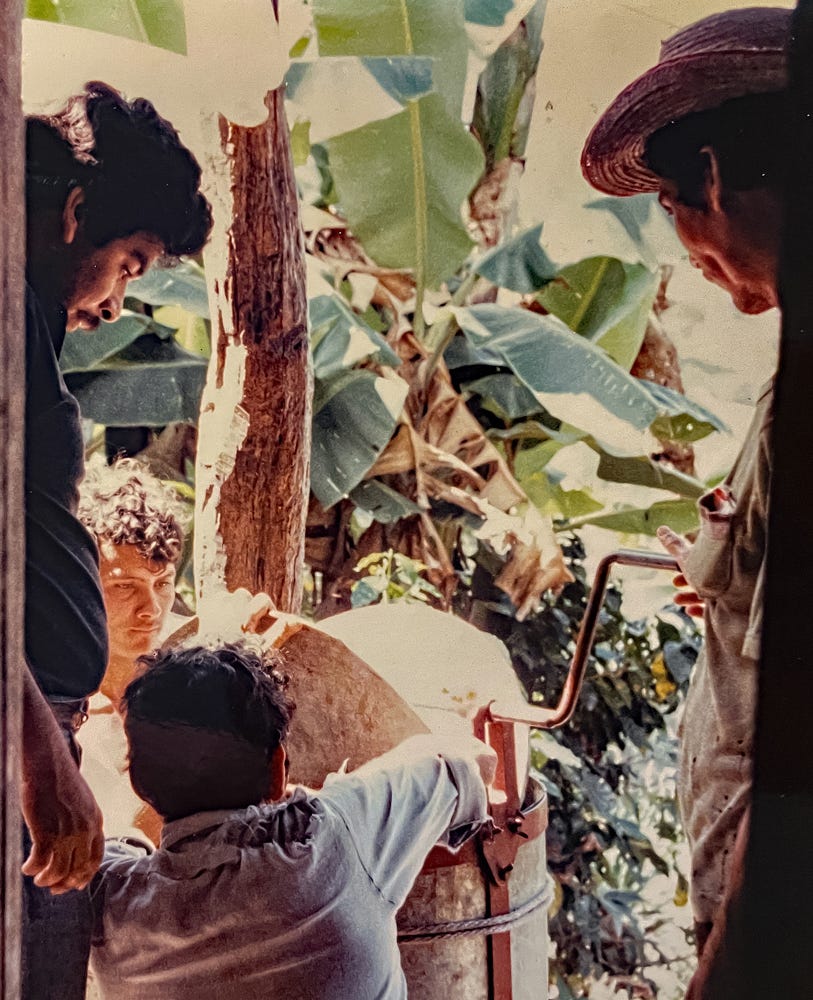

My career in international development (and photography, although unbeknownst to me at the time) began in 1983 with Cuerpo de Paz (Peace Corps), teaching modern beekeeping practices to Honduran farmers. Truly a fish out of water (bee out of hive?) experience, my three years as a Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) exposed me to a world about which I knew very little. Of course, I had seen poverty, hunger, and despair, but now I was forced to ponder some vexing questions; starting with “what is my job, anyway? How can I help these people? I signed up for three years of this!?” Living among the farmers with whom I worked, and taking my cues from them, eventually helped to define my work. And over time, I learned to appreciate that they had as much to teach me as I, ostensibly, them.

Nonetheless, dilemmas related to development work remained. Most, if not all, PCVs are met by ambiguity, having to navigate a mystifying, often perplexing culture and job that exists in title only. Language barriers and most PCVs’ relative youthfulness conspire to test even the most motivated. And therein lies another dilemma: in U.S. society we learn to define ourselves by the work we do, the ability to meet deadlines, stick to schedules, and “get shit done.” Not so in many other cultures. The work ethic with which we’re brought up in the U.S. is not necessarily shared throughout the world. Certainly, not everyone outside U.S. culture defines themselves by their jobs. That ambiguity and inability to be flexible leads about a third of all new volunteers to return home before completing their two-year stints.

Honduras in the mid-1980s was a politically fraught time. My attempts to flee the Reagan political machine were thwarted by the U.S. government’s support for the contras fighting the Nicaraguan Sandinista regime. As PCVs flooded into Honduras, we found ourselves unwitting participants in a “hearts and minds” campaign to maintain and strengthen U.S. influence in the country and region. I’d watch in dismay as U.S. Army transport planes flew over the capital, Tegucigalpa, with alarming frequency. Soon, “Yanqui Go Home” graffiti began appearing on walls in the major cities. Meanwhile, with over 350 Volunteers stumbling over each other, there weren’t enough sites to place them all, much less the requisite number of “jobs” needed to accommodate them.

Somehow, though, I was able to carve out work for myself, maintain distance from the U.S. military presence, and avoid socializing too frequently with other PCVs. The unfortunate effect of the build-up led to many volunteers hanging out with one another rather than host country friends and colleagues: a practice that Hondurans dubbed “cuerpo de paseo” (vacation corps).

Peace Corps service is normally a two-year stint, but extending for a third year to help train beekeepers to work with the invasive Africanized honeybee (which had begun moving through Central America by the mid-80s) was a challenge I couldn’t pass up. Until then, I’d merely been training Honduran farmers in modern beekeeping techniques, but the highly aggressive, volatile Africanized bee threatened to upend the entire Honduran apiculture industry.

Modern beekeeping techniques are not difficult to master, and adapting those practices to Africanized bees was relatively straightforward. Introducing those concepts and practices to traditional farmers whose resistance to change, particularly when suggested by a 24-year-old kid, can be an insurmountable task, though. Indeed, many of us are reluctant to deal with new, unknown technologies, practices, or viewpoints. Why would it be any different in the context of international development work?

There was a moment, though, when I was convinced that my work was worthwhile. Of the two dozen apiculture projects with which I worked, one was headed up by a group of women and men whose extraordinary work ethic and curiosity about bees had long impressed me. In the middle of honey harvesting season, heavy rains and washed-out roads prevented me from getting to the project site to “oversee” the honey harvest. The worst-case scenario of not harvesting the honey could lead to the bee colonies swarming and abandoning their hives. Once I was able to get to the project (about a week late), I learned the group had procured a honey extractor, harvested and bottled the honey, and the bees were busy making new honey. I remember feeling both pride and relief that the group had forged ahead with confidence, and that my training efforts over the previous months had paid off (in at least this one instance). I was afforded a brief glimpse of what working myself out of a job could mean and of those two dozen projects, I like to think that at least one is still buzzing today.

I took two lessons from that episode, and my Peace Corps service in general. Regarding the first lesson, a colleague and mentor once told me that his work as a PCV teaching English as a second language was really about teaching his host country colleagues to say “no,” to be critical, to stand up for themselves, to be proud, and to not succumb to the interests of the wealthy and powerful. Subversive? Perhaps, but in a way that furthers progress and development. The second lesson was to say “yes,” to change, to the unknown, and to possible failure. Saying both “yes” and “no” takes courage, a trait I saw everyday among the people with whom I lived and worked.

Usually, upon one’s return from Peace Corps service, one is bursting with stories (and self-righteous pride) about the experience. Unfortunately, not everyone is interested in hearing those stories. I was lucky, though, as I was hired as a Peace Corps recruiter in San Francisco shortly after my return from Honduras so I could share my experience to captive audiences throughout the Bay Area. Working with a professor who also happened to be a Returned Peace Corp Volunteer (RPCV) at San Jose State University’s (SJSU) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies led to my eventual return to academia and an advanced degree in Environmental Studies. Interestingly, most of what I learned at SJSU mirrored and confirmed the connections between people and the environment I’d previously observed in Honduras. A couple years later, my return to Honduras would also be largely due to what I’d learned as a PCV. And that’s another story.

More later.

(All photos @Mark Caicedo/PuraVida Photography)

Have you given any thought to going back there now to visit and compare?

For years, a particular sore spot with me has been Reagan's political poisoning of Honduras (and arms deals in Nicaragua, etc) contributing a great deal to the ensuing migration of very worthy immigrants from those regions to the US. We should embrace, not reject, them.

This was fascinating. And the black and white of the beekeeper and his son is a true keeper. Curious: Did you think of editing the other photos of the people in the lower part of the piece and turning them into B&W? I think those would be striking portraits as well in that format.