In the two plus years since traveling in Tanzania, I’ve had plenty of time to reflect on that life altering journey. Much has changed since then: retirement; relocation; recareering, but the thoughts and feelings from those long hours on the savannah have lingered and continue to fire my imagination. And I long to return.

“Safari” comes from the Swahili ‘an overland journey to observe wild animals, especially in eastern or southern Africa.’ Originally from the Arabic noun سفر, 'safar' (to journey), a trip through the African bush is much more than just observing wild animals. Traversing that seemingly endless landscape, you realize just how utterly small and insignificant you are, what it means to be an outsider, and perhaps reassess your own place in the world. Overwhelming, indeed, but rather than focus on those unwieldy and frightening realities, I’ve tried to remember the fascinating details and stories found just below the surface.

When you step off the small plane after your flight from Dar es Salaam, the sense of anticipation is palpable: “when will I see an elephant…or zebra…or lion?!” Those expectations took me right back to childhood zoo visits, but in this case, that first sighting of a giraffe, or warthog, or crocodile in the wild is magic in a way no caged animal could ever be. Then, as your overland journey continues, bouncing down rutted dirt roads in a land rover, you’re flabbergasted by the sheer numbers and diversity of the wildlife around you. Humbling doesn’t begin to cover the kaleidoscope of emotions that overcome you while trekking through Tanzania’s wilds.

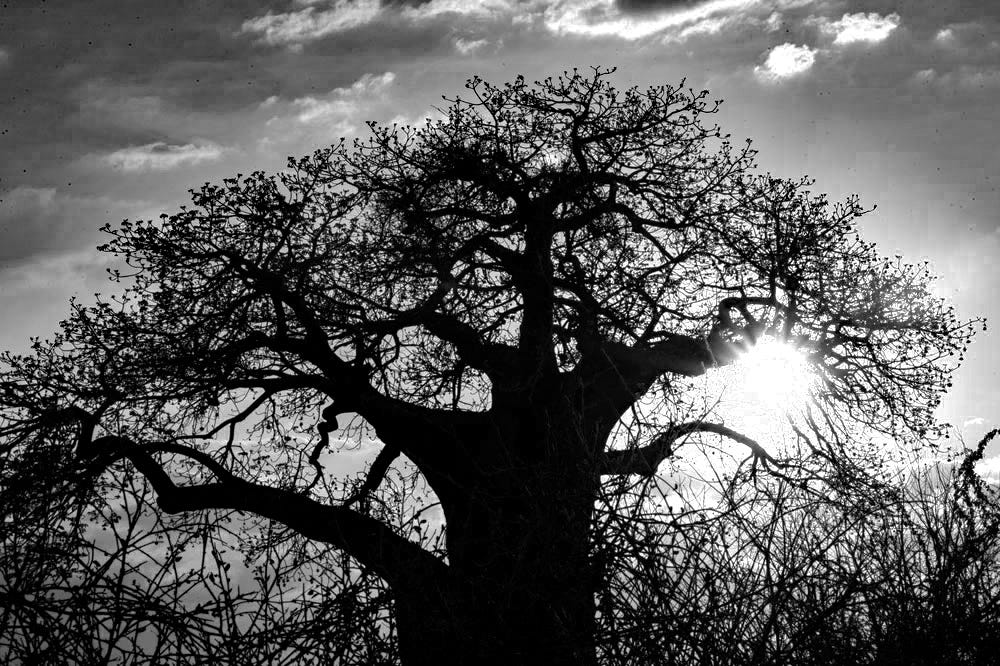

An East African safari begins with the Baobab tree (Adansonia digitata): Africa’s “tree of life.” These giant creatures provide water, food, and shelter in times of need and plenty and, because they can live up to 3,000 years, baobabs have seen their share of both. Their existence helps others survive. Elephants will strip their bark in search of food and water, or hollow them out for shelter (of which myriad other creatures will take advantage-including, ironically, poachers). Their broad canopies house countless birds, monkeys, and baboons. Termite trails snake up and down their trucks. Bees suspend their hives from the branches.

The hippopotamus or “river horse” is widely acknowledged as the continent’s most dangerous land mammal, killing about 500 people each year. Equally at home in the water or on dry land, they can grow to over 16 feet long and weigh nearly 10,000 lbs. Although one would never think to invade their territorial waters, hippos will wander out on land at night to forage, traversing well established trails that can result in tragedy should any human obstruct its path. Their massive jaws armed with huge tusks can slice hapless victims to ribbons. Hippos are anything but cute, tutu clad cartoon characters.

If you encounter a tower of giraffes, you can tell the males from the females by looking at their horns. Males’ horns are almost always bald whereas the females’ are completely covered with hair. Males establish dominance by fighting (a ritual called necking where they bludgeon each other with their heads and necks) and the hair on top of the horns often gets torn off. Females don’t fight, so they never lose the hair on their horns.

More giraffe fun facts: 1) the horns are actually called ossicones (horn-like protrusions) formed from cartilage that is covered with skin; 2) no two spotted coats are alike; 3) giraffes eat up to 75 pounds of foliage daily; and 4) in Tanzania’s Ruaha National Park, giraffes use long and extremely tough tongues to feed almost exclusively on Acacia trees, despite their extremely thorny branches. And as if needlelike thorns weren’t defense enough, once a giraffe has munched on its leaves for a while the acacia, to discourage further foraging, will release tannins that make its leaves taste awful and inhibit digestion. Even more astounding, acacia trees within a 50-yard radius react to their neighbors’ tannin release by emitting their own. The simultaneous tannin release by all nearby acacias essentially frustrates the hungry giraffe(s), forcing the animals to search upwind for “untanninized” trees.

Up close and personal encounters with big cats is perhaps the most thrilling of all African wildlife experiences. My first interaction with lions was this pair, the male of which my wife, Joscelyn, and I nicknamed Goldenboy. Lions breed throughout the year, with females usually mating with one or two adult males of their pride. Females are receptive for up to four days and a pair will generally mate every 20 to 30 minutes. Such extended copulation (up to 50 couplings in a 24-hour period) not only stimulates ovulation in the female but also ensures paternity for the male by excluding other potential mates. (Point of clarification: we did not spend our entire safari watching this pair “do it” for four days.)

The cheetah was easily the most gorgeous animal I saw in Tanzania, though she only stuck around for five minutes or so. Guides and trackers will share information on spotting animals so when our guide got the call, we raced across the park hoping to catch a glimpse of this magnificent predator. Following hankies placed bread crumb-like on a trail of bushes, we found this cheetah lazing under an acacia tree. After a few minutes, she’d had enough of the nosy humans and calmly trotted away, though not before leaving me with one of my most beautiful, vivid, and fleeting memories.

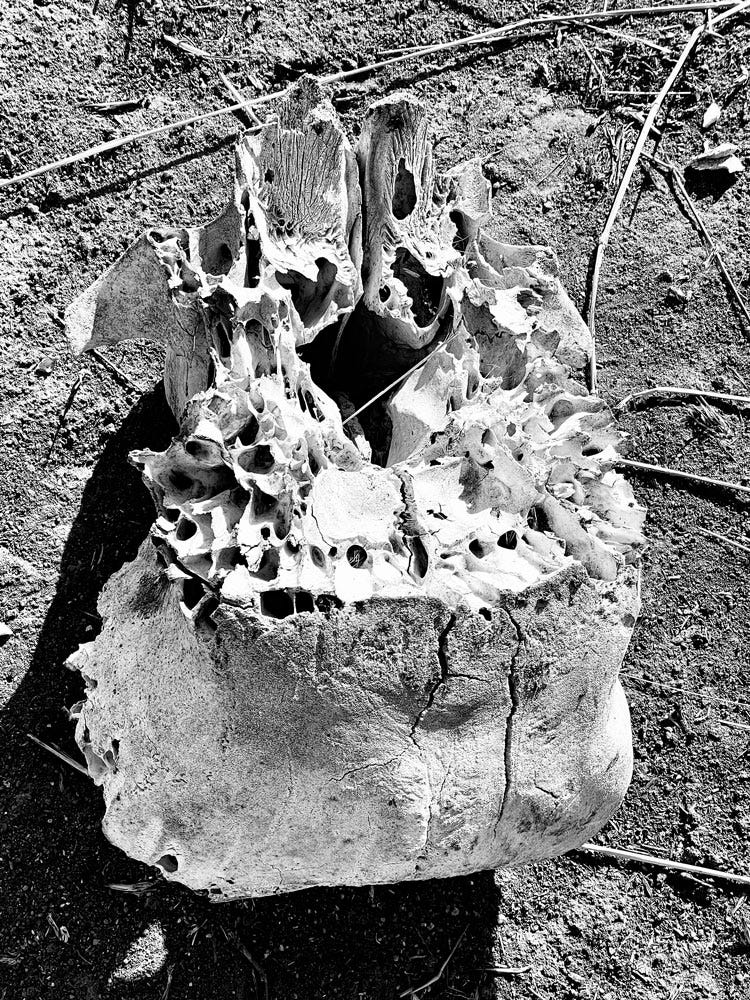

African elephants are extremely intelligent and formidable creatures. They are huge animals: males can stand 11 feet at the shoulder and weigh over seven tons (and, of course, push over a baobab tree). Their skulls are strong enough to withstand forces generated by the leverage of the tusks and head-to-head collisions. The brain is protected by arches created by the flattening toward the skull’s rear while the web of air cavities maintains its overall strength and reduces the weight of the elephant’s head.

Perhaps most striking about the African bush is the pervasiveness and immediacy of life and death…and poop. Hyenas feasting on a young buffalo carcass may be unappealing to some, but ultimately every atom of every carcass will be transferred to another living creature through the work of these scavengers. Although hyenas are one of the most unfairly maligned predators in the world, due to their adaptability and opportunism they are the most successful and widespread large carnivores in Africa. Once hyenas have gorged on their prey, including the bones, their ghostly white poop, rich in calcium, is consumed by tortoises whose eggs are then fortified by that essential element. Ingenious hunters and efficient scavengers with the ability to eat and digest flesh, skin, and bone, hyenas make the most efficient use of animal matter of all African carnivores.

Nothing, absolutely nothing goes to waste in this dangerous, beautiful landscape.

All photographs copyright Mark Caicedo/PuraVida Photography.

After reading this post, all I can say is, “I’m jealous.” 😑📷

Fascinating, and your images are incredible, especially the first and the last. I hope to do something like this someday.